At WebExpo 2025, Robin Pokorný delivered a talk with a deceptively light premise and a very real warning: dates and times are a trap-laden mix of physics, convention, and politics. His framing was immediate and disarming: “There’s a long-term pet peeve of mine. And that’s dating. And by that, I mean dates and times. I don’t have problems with dating otherwise. I’m happily married.”

From there, “Dating is hard: Complexity of clocks, calendars and computers” built a clear argument. Time is messy in the real world, many common formats behave unpredictably in practice, and newer standards plus upcoming APIs aim to make time handling far less error-prone for teams shipping real systems.

The “wall clock time” humans speak, and software struggles to model

Robin began with how people naturally express time: “It’s the 28th of May, 2025, two o’clock in the afternoon.” We instinctively add context like “Wednesday”, switch between 12 or 24 hour formats, and still understand each other. Robin called this “the wall clock time” and explained why it matters: “It’s a local time. I like to say local time. And that’s where we humans operate.”

The trouble starts when software treats local time as something you can store and replay later without ambiguity. It’s often not, because “dates are so complicated… because we have a mixture of things that are natural and things that are human-made.”

Nature didn’t promise an integer number of days in a year

Robin’s core foundation was simple. A day and a year come from different physical processes, and nothing guarantees they will align neatly. “Now, the problem is we expect that these things are connected. And we expect that they would play together well. But there are, in its essence, completely independent phenomena.”

The consequence is the reason calendars exist at all. “What it means is there are no integer times of days in a year. What is worse, that’s actually really crazy, is that it’s not even constant. It changes.” Our systems crave certainty, but the nature doesn’t offer it.

Leap years were only the beginning

We’ve already accepted that calendars need patching. Robin pointed to the Gregorian calendar as “a really good approximation” and reminded everyone how many rules are required to keep “year” and “day” aligned to seasons. But when computing enters the picture, the demand for patching doesn’t stop at days.

He explained how we chose a clock system on top of natural cycles: “We created a clock. We divided that day… And we said, OK, let’s do 24 hours. But this is an arbitrary number.” Then reality intrudes: “the length of a day varies.” That leaves an awkward choice: “You either use that second you defined before. But now the day doesn’t have those 86,400 seconds. Or every day you redefine what a second means. That’s not great. We did both, actually.”

Leap seconds are the outcome and they create a nasty edge case: “How you do that is that you have 23.59. 23.59.60. 00. You have a valid date time that ends with ‘60’ and the position of your seconds.” It’s the kind of “valid” timestamp that still breaks production systems.

Time zones are politics, not maths

If leap seconds are the physics problem, time zones are the political one. Robin didn’t sugar-coat it: “And then we have political changes. And these are actually the worst. I’m talking about time zones.”

His point was not about daylight saving preferences but unpredictability. “Chile, in the year 2015, till the year 2019, in four years, they change the number of times as they have… Several times, sometimes even noticing within months that the change will happen.” That makes long-term planning extremely fragile: “That means that any time you wanted to plan something, you couldn’t, especially when you’re talking computer time.”

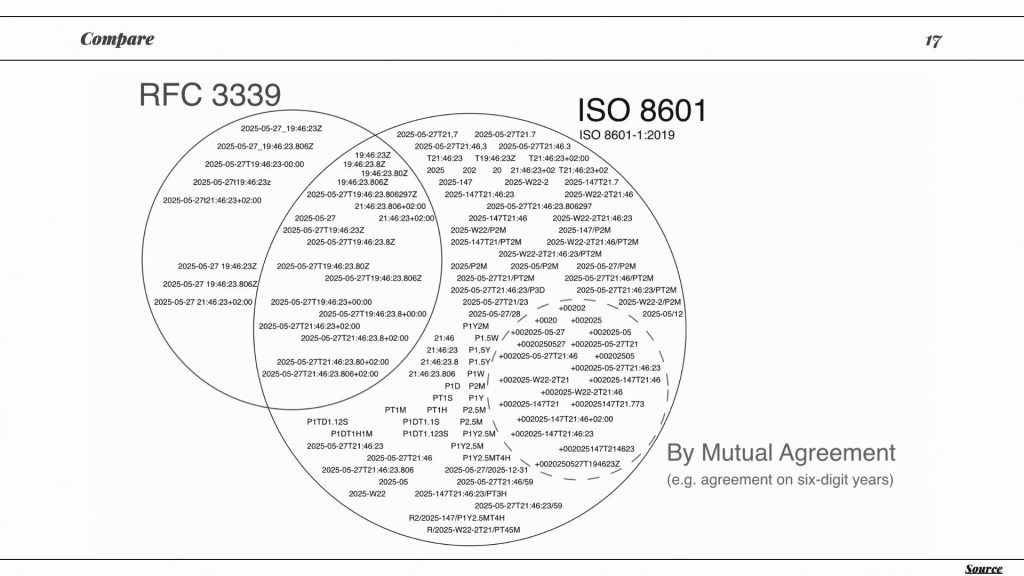

ISO 8601: famous, flexible… and a trap in the real world

Next, Robin turned to the format many teams reach for by default: ISO 8601. Despite the familiarity, he was blunt: “I want to tell you that it is something you should not be using.” Why? Because “valid ISO” is bigger than “what parsers accept”. “This is a valid ISO date. And what I discovered is that most parsers will already fail on this.” He clarified that the format itself is not wrong, only a poor foundation for reliable system design. “All of this is very valid. There are use cases for this. What I’m trying to tell you is that this is not something you want to use.”

Then came the detail that landed hard: “On top of that, ISO 8601 is a paid standard… And it costs 170 Swiss francs to buy it, to read it.” Multiple versions and compatibility gaps only amplify the risk. His practical takeaway was: don’t anchor your API contracts to a vague “ISO 8601” promise.

Timestamps aren’t a magic escape hatch either

Unix timestamps look like the “simple” answer, yet Robin showed how quickly they become ambiguous. “We are measuring time from the first of January 1970, but in which units are we using seconds? Are we using milliseconds? Is JavaScript that by default? Are using nanoseconds…”

He also returned to leap seconds and monotonicity: “What it does, that it runs the same second twice.” The stakes aren’t theoretical: “In 2015, a stock exchange had to close down because the leap second was introduced… So they stopped, they’d rather stop trading… just to make sure nobody gets an extra advantage.”

The practical direction: RFC 3339 and IxDTF

Robin recommended RFC 3339 as a safer baseline for representing instants, describing it as “a free standard, and it removes some of the ambiguities.” Mandatory separators and offsets remove a lot of “close enough” parsing chaos.

For scheduling, recurring events, and anything where “local time” should remain meaningful even if rules change, he introduced RFC 9557 / IxDTF. The key improvement is attaching a real time zone identifier (city-based), enabling consistency checks and better long-term interpretation. “What it allows me to do, and that’s an awesome thing, is that now I can check for inconsistencies. And I can decide if I reject that date or not.”

Temporal: the API layer catching up

Finally, Robin tied standards to tooling with the upcoming Temporal API in JavaScript. It promises less fragile time arithmetic and clearer modelling framed as “a full replacement for a day object.” He also mentioned the adoption progress: “Firefox fully supports this out of the box. It’s being developed in Chrome… And eventually, Safari will follow as they always do.”

For teams building APIs, scheduling, reporting, audit logs, or anything involving human time, Robin’s message was clear. Time handling is not a formatting decision. It is a design decision. For more detail, see the video recording and slides: